The Concord: An Album

Originally published in 2007

In early August of 2002, with nearly a dozen songs in hand, the Concord reserved Saturdays and Sundays of the next six weeks for the making of an album.

Two locations were chosen. At the first, Michael's church, most tracks would be recorded; at the second, an auditorium on the nearby campus of Baldwin-Wallace College, Jonn performing on a dulcet Steinway grand piano.

Following a schedule for every part of each arrangement, combinations of the five members would meet and for long hours bring their music — which was never captured live — into a state of permanence.

The church, from its decades of ad hoc expansion called a "rabbit warren," provided countless acoustic possibilities with many shapes of rooms, corridors and stairwells.

Of these, more in the interests of simplicity than modesty, the group picked just two — a smallish, square room used for main tracking and a large gathering hall for heavy natural reverb.

Equipment was situated on the closest tables handy, in whatever space was most convenient. "It wasn't fancy," notes Michael. "It was practical."

After matters of logistics had been settled and the band confirmed that all equipment could reasonably be transported for a weekend's work, the two-day sessions assumed their own routine. On Friday evenings, Michael and Charlie and others would drive up to the church and deposit all the gear necessary for recording the next day and Sunday. These nights would sometimes end late, owing to a long chat or spontaneous jam.

Sessions began around eleven in the morning, and regularly lasted until eight at night. Here the group's rapport made the time pass easily. Lunches and dinners were often taken at Café Stratos, a restaurant several blocks down the street.

"The process moved steadily forward," Michael remembers, "but was rarely tense, thanks a bit to only one of the five — me — not being laid back, though mostly because of our sense of purpose and appreciation of time limits, however leisurely we might have been tempted to work in facilities that came free of charge."

By the end of September 2002, the Concord had finished twelve tracks, one cover song and eleven originals.

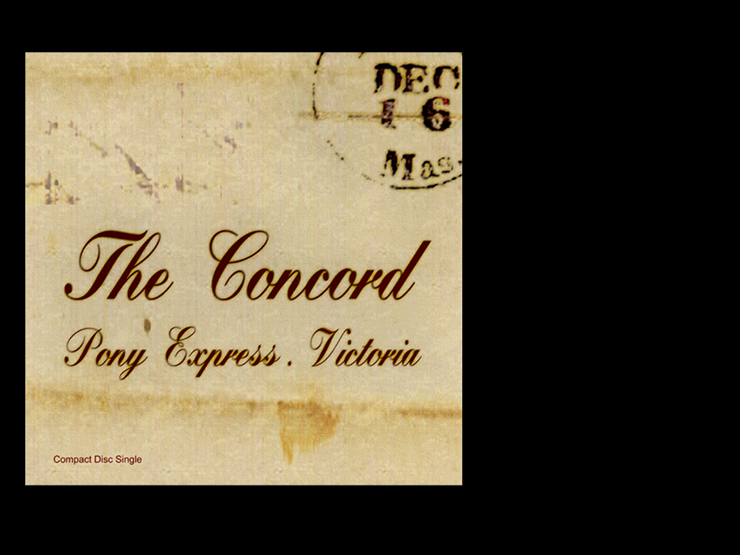

Pony Express

By coincidence in design, the first product of the five-piece band was in a style and length suitable for leadoff place on both setlists and the album's track order. "Pony Express" barely clocked two minutes, a single chorus resolving two verses of light-heartedly wry reflection.

It was so apt as a succinct musical statement that the band, asked to play an encore at its debut, succeeded by offering up "Pony," the song played half an hour before.

Work began in Dave and Michael’s one-on-one sessions in early 2002. Dave chose a countermelody to the main riff and a moving bass line for the rest of the song, selections that influenced the contributions of the other members.

"At first, 'Pony' was interesting but not exciting, each one of us playing his own variation of the same thing," Michael recalls.

"Then Gabe, who was holding power chords over the eighth-note rhythm, tried a syncopated melody based on thirds. The song had its motive, and through Gabe's use of delay and chorus, a sound that reached back to the best of 1980s New Wave."

The complete song was infectious. "As soon as Gabe found his signature part, we played through 'Pony,' hit the stinger at the end, looked at each other with big grins and wordlessly started up again. We did that about a dozen times."

"Pony Express" was the band's first and only single, released twice: once with a B-side cover, the Kinks tune "Victoria," and again with the latter plus an early mix of "Archie."

The band had an opportunity to match its style with a colorful jacket design that included a felicitous snapshot of a cowboy swingset, taken by mutual friend and photographer Paul Levar.

Notwithstanding tiny audiences and a tinier budget, the singles sold well.

Archie

An offhand, sixteen-note melody written in Michael's final semester of college was, during the months of 2000, expanded into an ornate score for piano. Set to dub-style bass and a clip of John Bonham's touchstone drum introduction from "When the Levee Breaks," a demo was sent to Gabe, who added arena-strut licks on the electric guitar. With the addition of the other three members, "Archie" became a flamboyant but memorable anthem, an imaginary Great War remonstrance as delivered to a carouser by his fellow dandy.

It is in this track, as well as "Barking in the Street," that Jonn's virtuosity and invention on piano, mixed front and center, are plainly that which separates the Concord from any other kind of clever-enough progressive rock.

"Much like with Dave, Jonn has the ability to elect not to play a passage the same way twice. That makes composition and recording easy and, depending on what either can dream up, rewarding."

The final version "Archie" was the last to be mixed in the studio — its greatest challenge was, inconveniently, the engineering of Charlie's drums, which Michael considered central to the track's rhythm section.

"If anyone can bang a snare and kick like Bonham, it's Charlie. But how do you capture an unmistakable sound without merely aping the treatments that originally produced it? After a lot of fiddling, we had something: a combination of the performed track and triggers of varying timbres and ambiences, heavy compression in key places, and a touch of distortion. Maybe a little too bright, or close, or big, but for 'Archie,' it was what pretty much fit."

Saltpeter

Announced by an eerie trickle of piano notes atop a chorused roar, and concluded with the delicate reprise of an otherwise insistent melody, "Saltpeter," moody and theatrical, stands as the Concord number with intensity to spare. Like "Archie," the first incarnation was a short, lyrical motif that was swept up in the spirit invoked by Gabe's response to it: this time, garage-rock.

Recording is a compromise of time and energy, and when "Saltpeter" was mixed it was decided that tracks laid down for the guitar solo were technically correct but sonically dull. They would have been acceptable if an older recording in the church, from a year or two back, hadn't been preserved. That prior session, Gabe chose to use acoustic strings on his electric guitar, resulting in a peculiarly thick — and haunting — sound. A few splices were made to account for different tempos, and the insertion was complete.

Despite the solemnity, even the darkness, of the lyrics of "Saltpeter," an alternate chorus emerged at some point in the disorganized basement-jam days of 2001. "Where it came from is unclear, but its heading was thoroughgoing parody. Something about a robotic lizard from space and a villain identified by a lineamental scar. Attempts by any one of us to piece together complete verses were abandoned on account of leaving the joke to rest in implication."

The Month of May

A funk beat, a bass throbbing like a foghorn, wah-wah, honky-tonk piano, a tambourine and a barbershop trio: this was the chimera known as "The Month of May." The song was first performed as a leadoff, compelling the audience to judge by preference.

Those expecting to hear the Concord enjoyed it — during a show some weeks later, the bar's proprietor was spotted dancing.

Other, less affirming opinions included one from the drummer of a band setting up afterwards: "People who don't play normal music should be dragged out into the street and shot."

Producing "The Month of May" brought a special challenge. "If I wanted," says Michael, "I probably could have mixed the song straight, as a translation of the live sound. But there were too many possibilities in exaggerating the difference between the bumptious verses and gentlemanly choruses." For verses, Charlie's drumming was chopped up, layered, looped, mixed with percussion samples from onetime collaborator Eric Wahl, "with intent to create a kit that sounded twenty feet tall."

Choruses were stripped down and involved the hard panning of bass and drums — one in the left speaker, the other in the right — a subtle nod to the techniques used in Vince Guaraldi's Jazz Impressions of a Black Orpheus.

"Dave commented that 'The Month of May' was a perfect snapshot of the band, with about half a dozen styles and twice as many textures. Like the Concord: eclectic and angular, yet it all hung together. He was right."

And June

At about the same time the album's assembly showed the need for an interlude, Michael completed a short chamber piece for piano. Set in the style of French composer Charles Koechlin, the ninety-second, pensive complement was positioned in the immediate wake of "The Month of May." It served as a transition from the vigor of the first four tracks to the more brooding "Margin," and dubbed "And June."

Jonn performed the art song on a quaint upright located in the church's hall.

"The evening we chose to record, a terrific rainstorm lurched through the area. So, on top of the squeaks and creaks coming from the building's tar roof — which had already made their way onto tracks — there were now the sounds of thunder and passing cars as they ran through puddles and sluiced the main street. While Charlie and a friend watched, and I discreetly inquired where to go to ground in case of a tornado, Jonn played 'And June.' In two takes, we had it."

Margin

Dating from the summer of 1999, "Margin" was built around a short saxophone melody played to a drumbeat in 7/8-time. As a set number and studio track, it retained its initial qualities — idiosyncratic, sparing arrangements — more than any other Concord song.

"Margin" did benefit from some developments. For the stage, Gabe wrote an entirely new guitar part, and Dave substituted more natural bass lines. Michael notes, however, that the largely verbatim reading was a compromise.

"The strength of 'Margin' lay in its novelty. Here I was, a saxophonist, with neither experience nor aptitude for jazz, handling my instrument more like a French horn, writing with jazz in mind. The others spent time trying to make heads or tails of it. Our decisions were mostly cautious and we lost, I think, the chance for some improvisation. But by using a light hand, we let 'Margin' be what it was — a unique little tune."

Recording provided opportunities for creativity. Gabe used a reverse-echo effect on the guitar, while Charlie's kit was captured with a minimal, three-microphone technique. Dave borrowed a bass fiddle, plucking and bowing through his part. Michael built up multiple tracks of saxophones: a velvet septet in one section, a wailing chorus in another.

When it Was Real

Though origins of the band's oldest song were not as distant as those of "The Month of Way," the onstage arrangement of "When it Was Real" turned out quite a ways from the electronic experimentation and techno aesthetic that defined early mixes.

Live drums, guitar and bass had been added to the track for the 2000 compilation, and by the time it was recorded in the church sessions, "When It Was Real" was in earnest a rock song.

Most sequences were translated into parts played by the five members, though not all. One notable remainder of the version from 1998 was the ataxic synthesizer bass line introducing the song — inspired by Nitzer Ebb's album That Total Age, and accomplished by setting a short recording of a bassoon to an impossible melody before torturing the result with overdriving and phase sweeps.

"We wanted Gabe's guitar to have some real power, and were encouraged by how well Gabe's Peavey responded at volume levels to which it had never, in practice or on stage, been pushed. Dave gave each knob one clockwise turn after another. The sound coming from the amp became so incredible that Dave and I took Gabe aside, placed a second pair of headphones over his ears and taped a towel to his shirt. He looked like an insect."

The recording, unfortunately, only partially reflected pains taken. "And then, a few months later, the Peavey died. Dave and I were never directly blamed, which we credit to Gabe's charitable nature."

Faith, Boy

In 1999, Michael and Gabe combined a metric upbraiding the Irish Republican Army to a simple melody in 5/4-time, following Michael's having served coffee to a young man who claimed to be raising money for Sinn Fein.

The first mix's drums came from a recording of Gabe beating on a kit every which way, as hard as he could, the unforgettable energy of which led each of the song's several realizations.

Supporting backing vocals by Gabe and Dave, ensemble chants consisted of Michael, Gabe and Jonn. The three sang several times through, and then tracks were spliced and placed on top of each other. The chorus voices totaled in the dozens.

Least harmonically complex song of the eleven, "Faith, Boy" was comparable to the others in its odd-beat rhythms, Dave's lively bass work and the ethereal heights of Jonn's keyboards. It was, and yet wasn't, straight-ahead. Deducing an Irish influence, however, would be inaccurate.

"None of us knew much about Gaelic folk music — other than that one could approximate it with a certain reliance on roots and fifths, and so 'Faith, Boy' was indirectly and mostly unconsciously of that manner. But looking more closely, the vocal arrangements, especially in the refrain, come off rhythmically like a jig."

Barking in the Street

Only through the so-called universal language of music could a song be transposed to vintage, lovelorn rock from an electro-thriller heralding the abhorrent birth of the Third Reich.

Recognizing the melodic and rhythmic value of this track from the 2000 compilation, titled "Those Persuaded," Michael cannibalized the song and introduced a classic account of boy-meets-loves-loses-girl. At an early jam session, Dave added a bass groove reminiscent of The Animals, and "Barking in the Street" was made prospective repertoire.

The name of the song itself came from a literal observation made by Gabe one night — Michael vowed to write a song around the phrase, something made possible by the inception of the quintet. Instructing the band to work through a progression and elaborate, Michael singled out Jonn for any piano acrobatism he could fit in — and Jonn delivered.

"The narrative moved, turned and finally resolved on Jonn's playing. Four verses representing as many scenes came from the lyrics first, but listening to the final track, the words seem to follow the piano."

"Barking" was probably the most difficult song to play and record. Dave's sixteenth-note part, a workout in its own right, was painful to play if the song started on the fast side. Gabe and Jonn each made comic blunders while laying down solos — clips of which found their way onto a bloopers tape.

Charlie performed his drums for the song last, in that first recording session, at the end of a sultry August day. "Exhausted, maybe even dehydrated, he began fumbling, then he forgot what to play altogether," remembers Michael. "I was, in a word, unsympathetic. Gabe was luckily nearby, and mercy prevailed. We helped Charlie through the rest of his part and the hell out of that stifling tracking room."

Ellis Island

Another product of trading and rewriting, "Ellis Island" was originally a short demo of Gabe's. It sat for months before Michael changed the sketch's tone from menacing to meditative, replacing the given single stanza and refrain with his own, full set of lyrics.

Rehearsing and recording with Jonn in 2001, Gabe and Michael brought in piano and definitive guitar treatments. Dave and Charlie, learning the song, made their own subtle additions.

On every setlist and, finally, the album, "Ellis" came second-to-last.

"Reflective, contemplative — a breather and a rest for everyone's ears — the song fit perfectly."

Michael notes: "It was at one of these 2001 sessions that a coincidence took place. Considering several topics for use with lyrics, I chose my grandfather's emigration from Italy — as seen by another passenger, a stranger. Grandpa died the morning of July 14th. As the flight to New York City for the funeral would not leave until the next morning, and Gabe and I had already planned to record some of 'Ellis,' we did so. It was an apt two-man memorial."

The Spectacle

A musical leap of faith, "The Spectacle" was presented by Michael to the other four members in such an elemental state that authoring was, more than any other song, coequal. Resulting in a creative process that required more time, finer judgment and closer cooperation, the success of sharing responsibility affirmed a fellowship as strong as the band's skill and efficiency.

Though uncertainty would continue until the last note, a number of events seemed to keep "The Spectacle" in favor from the song's introductory rehearsal. Michael played the hook, "and was about to attempt to describe the bass line I wanted Dave to play underneath when he put a 'What do you think of this?' look on his face and started plucking almost exactly what I wanted him to."

Elsewhere, the quintet worked methodically as a team. "I asked for a series of weird meters right after the first verse. Gabe stepped in, suspending a melodic arc across the entire phrase. The other three moved in to harmonically and rhythmically brace it. What was arbitrary, they made a great musical device."

In the studio, liberties could be taken with a song consisting of three distinct movements.

The entrancing solo guitar would be accompanied by an atonal series of sine-wave pulses — Michael wrote a simple program to generate random numbers and note lengths, then sequenced the results.

Asked to respond to music of minimalist composer Steve Reich, Jonn programmed a marimba ensemble. Charlie performed in both the small tracking room and large hall. Dave made use of a loaned five-string bass, resulting in the second movement's preternatural growl. Gabe, dutifully, played a drone melody with trademark precision.

"All of five of us would agree, I think, that 'The Spectacle' brought a fitting close to the album and, being as it was the last song in our working relationship, the band. We assembled, we played, we concluded. In twelve months we created and left behind something totally unforeseen the year before. Recalling the Concord five years later entails an act of observance."

Return to homepage.